Abandoned - not forgotten

St Govan’s Chapel at Sunrise, Pembrokeshire, Wales

Legend has it that an Irish monk called Govan was sailing to Wales when

he was set upon by pirates near Lundy Island. A cliff opened up and left a

fissure just big enough for him to hide in until the pirates left. He decided

to stay in this rocky hermitage to warn the locals of future impending pirate

attacks.

Govan died in AD586 and is thought to have been buried under the floor

of the cave that is immediately to the east of the wonderful little chapel

built in his honour in the 13th Century. Some think Govan may be Gawain from the

Arthurian legends.

This iconic chapel blocks the entire path down to the sea and is now

reached by 52 rocky steps. Never was a place so steeped in Celtic mystery and

charm, made all the more precious by visiting it at sunrise. Nearby in the jagged

limestone cliff-face of Saddle Head lies Ogof Gofan, Welsh for Govan's Cave. This is

one of the most richly decorated natural caves in Britain and only visible and

accessible by a risky abseil down the cliffs. Standing on the grassy clifftop it's hard to imagine what lies just ten’s of metres beneath your feet and

hundred’s of years before your birth. Awe inspiring.

The Chapel Bell. Music inspired by St Govan's Chapel.

'The Chapel Bell' is a traditional Irish jig. Music arranged, performed and recorded by Keith. The sounds of the sea, seagulls and chapel bell are from the BBC Sounds Archive, the bell is from the chapel on Iona.

Played on tenor banjo, bouzouki and mandolin, with sampled Creative Commons bodhran and vocals from Arturia Mellotron and other effects from Arturia Pigments.

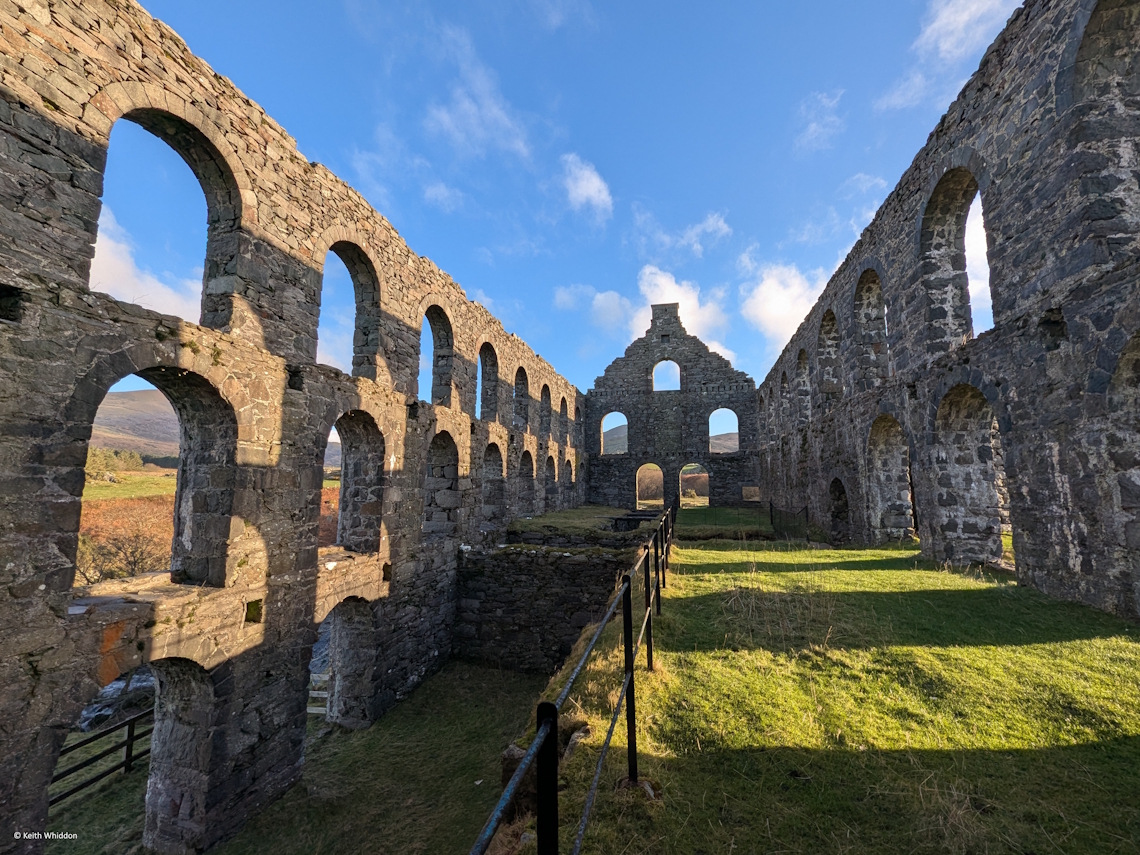

Ynysypandy Slate Mill, Cwmystradllyn, Gwynedd, Wales

Not far above bustling Porthmadog lie the remote and beautiful valleys

of Cwm Pennant and Cwmystradllyn. In the 1850’s Gorseddau Slate Quarry was developed

at the head of Cwmystradllyn. The company had big ambitions and raised a huge amount

of investment to spend on mining nine terraces supported by counter-balanced

inclines; a state of the art slate slab mill (‘Ynysypandy’); a beautifully

constructed gravity/horse tramway from the quarry to the mill and on to

Porthmadog, a village (‘Treforys’) for the workers comprising eighteen pairs of cottages on three streets. However, the slate was of such poor quality

that the whole enterprise closed by 1867 never having made a profit.

Ynysypandy Mill is a massive, three-story water-powered slate slab mill

designed by engineer James Brunless, later responsible for designing the São

Paulo Railway in Brazil. It was built in 1856-7 and is a most impressive

building, perhaps based on the large cotton mills of the Industrial Revolution

in Lancashire. Now it is more like the ruin of a medieval cathedral than an industrial building, which is perhaps fitting as it lies on land previously owned by an Augustinian priory. Today this beautiful ruined mill, next to the mountain

stream that provided its power, stands as a monument to the ambitions of the Industrial Revolution.

Cwm Bychan Aerial Ropeway, Nantmor, Gwynedd, Wales

In a remote and beautiful Snowdonian valley lies a metal construction looking for all the world like something out of the computer game 'Riven', or from some steam-punk film.

Cwm Bychan copper mine started in the 1720’s and closed in 1875. However, in 1925 the Nantmor Copper Company reopened the mine and installed a remarkable aerial ropeway to carry the ore in buckets one mile down the valley to a processing plant next to the newly opened Welsh Highland Railway. At the upper end by the mine (shown in the photograph), an iron tower supports a large horizontal wheel around which the cable passed. Buckets were suspended from the cable, each with a pair of wheels held by a friction device attached to the wheel carrier. When the suspended buckets arrived at this terminal station, they were automatically lifted by their wheels onto a fixed iron track passing behind the horizontal wheel. Here they could be stored temporarily while being filled, after which they could be manually pushed around the iron track, before being slipped back onto the moving cable. Apparently on their journey down the steep route the buckets had a tendency to flip over, tipping out their load!

The ropeway only lasted four years as in 1929 the mine closed permanently. However, much of the ropeway remains, including some of the supporting pylons and even sections of the wire rope. It now stands as an incongruous reminder of the valley’s industrial past.

Thomas Roberts of the Wild Hill – Bryn Moel, The Alltwyllt, Conwy Valley, Wales

I introduced my great grandfather Thomas Roberts in Lost Worlds 2024. The first record I have of Thomas goes back to 1861 when he was living at ‘Bryn Moel’ above

Dolgarrog, with Joseph Roberts and Joseph’s sister Ellinor. It is not clear who

his parents were, or if he might have been orphaned, as Thomas is listed as

being a boarder and a labourer, despite being just seven years old. Interestingly,

Thomas later called his own son, my grandfather, Joseph.

Last

October I tried (in vain as I now know) to locate the ruins of Bryn Moel

amongst the huge rhyolite boulders, dense undergrowth and forest that now

covers the steep hillside known as ‘The Alltwyllt’, or ‘Wild Hill’. However,

thanks to the help of the owner of the nearby

Porth-Llywd Pottery, who has researched the history of the area, I have finally been able to find Bryn

Moel. Its walls made of local stones are still standing, but its roof long

since gone and the whole site very overgrown and hidden.

In

1930 The Allwyllt was described as, ‘a densely settled area of irregular enclosures

and cottage dwellings abandoned at the end of the 19th Century. The dwellings are

built of local field-stones and have become roofless and severely dilapidated.

There are traces of field systems in the undergrowth. The holdings are

connected by a complex series of zigzag pathways. The cottagers made use of

donkeys to carry fuel and other necessities along the paths. They made their

living by knitting stockings, basket-making, as carriers, hone-quarrymen, sulphur

miners, household servants and fishermen’. Bryn

Moel was inhabited in the 1890's by a Robert Roberts, his wife and eight children - how did they all fit into this tiny cottage?

The notorious ‘Gwylliaid Cochion Mawddwy’ / ‘The Red-Headed Brigands of Dinas Mawddwy’ were a band of highwaymen and bandits living in the Dinas Mawddwy area during the 16th century. It is said that they were named for their red hair and their unruly ways. They murdered the Sheriff of Meirionnydd and for this they were rounded up and many were executed. The remainder were banished from the area and local folklore says that in the 1560's, the surviving members moved north and settled at The Alltwyllt, where they carried on their traditional garden type of agriculture, keeping cows on the common, mining and fishing. Their lifestyle certainly fits with the evidence of the way people

lived here last century. It might account for the numerous red-headed people

now living in this area and perhaps I might even be a descendant of the famous

‘Red-Headed Brigands’?

On

my way back down the hillside I bought this beautiful

bowl that had been glazed using ashes from the potter's own fire. Imagine my amazement when I learned that these ashes were of wood cut from the trees that grew where Thomas once lived as a child. A treasured and special

connection with the past.

The Great Klondike Mine Scam, Trefriw, Conwy Valley, Wales

Geirionydd Mill, as it was originally known, was constructed in 1900 by the Welsh Crown Spelter Company to process sphalerite, or blende, used to make zinc for spelter. The ore came from the Pandora Mine some two miles away and linked by tram and an aerial ropeway that entered the top of the mill. It was an ambitious state of the art undertaking, the largest of its kind in Wales. However, Pandora didn’t prove profitable and by 1911 both mine and mill had closed down.

The derelict mill was purchased by Joseph Aspinall in 1918. Aspinall published an article in the Mining Journal declaring that his company had discovered a very rich silver lode and how his mill had the modern machinery necessary to process it. He paid for rich investors to travel from London to view the undertaking for themselves. However, Aspinall had dressed up the insides of an exploratory mine entrance next to the mill by glueing tons of lead concentrate he’d brought in from Devon to its walls to make it sparkle and look like silver! He employed local men to run around and look busy and he even installed an old stone breaking machine inside the mill to create a lot of noise and make it appear to be at work.

This scam was however revealed to Scotland Yard by the owner of the nearby Parc Mine and Aspinall was sentenced to two years in prison for having deceptively obtained more than ten million pounds in today’s money. The scandal caught the public’s attention and the mill and old mine entrance have since become known as ‘Klondike’ after the famous Canadian Yukon ‘Klondike Gold Rush’.

The mill was a large concern, but the ruins are now in a poor state of repair. Today the barred entrance to Klondike Mine is reached by balancing along a narrow plank of wood across a stream. Waste material from processing the zinc ore covers an extensive area below the mill - so toxic that even today nothing grows on it. However, the lovely Afon Geirionydd upstream from the mill is now a popular gorge walk and scramble. Along its banks lie several short mine trial entrances, all testifying to the optimism and failed ambitions men once had for making money from these hills.

Abandoned Lock Keeper's Cottage, Dolfor Lock, Newtown, Powys, Wales

Construction of the Montgomery Canal began in the late 1700's where a branch was constructed off the Llangollen Canal. By 1819 the thirty-three mile route had opened all the way to Newtown. Unusually, the canal was built to bring goods into the area, its main purpose being to transport lime, as a fertiliser, to help to improve agriculture in the Upper Severn Valley. It fell into disuse following a breach in 1936 at its northern end.

The 'Monty', as it is affectionately known, is gradually being restored with government and private funding and Newtown may expect to be reconnected to the national canal network within the next ten years. The section north of the town remains delightfully derelict, leaving relics of its engineering legacy to be discovered in the undergrowth.

The Hoffmann Lime Kiln, Llanymynech, Shropshire

Lime

was a major constituent in making mortar for ancient buildings. ‘Quick-lime' was

made in kilns loaded with limestone and charcoal, coal or coke

and burnt for many hours.

In

1858, German inventor Friedrich Hoffmann patented The Hoffmann Kiln which revolutionised

the industry by enabling continuous, large-scale lime production. It is a large

brick construction with a main fire passage surrounded by smaller chambers,

allowing for continuous firing and efficient heat utilisation.

Today

there are only a few Hoffmann kilns remaining in the UK. The one near Settle (second below) is in quite a ruinous state, whereas the Llanymynech kiln (directly below) is now a heritage site. It was built in 1899 and worked until 1914 when the introduction

of Portland Cement replaced the use of lime in the construction industry.

Today

the Llanymynech Hoffmann Kiln is an impressive, cavernous structure, but life

for the men who worked inside these kilns was grim. They had to endure extreme

heat and toxic lime dust. Little wonder that their life expectancy was just 35-40 years.

The Hoffmann Lime Kiln near Settle, Yorkshire

Top

Top

© Keith Whiddon 2023 - 25